Biosolids: the good, bad and ugly

What we aim to do with biosolids vs. what's actually happening

I've considered writing about biosolids for some time. It's a controversial topic with some claiming they’re an environmental solution and others insisting they’re harmful to public and environmental health, with some claims diving into conspiracy theories that suggest the government is highly involved and intentionally causing harm.

Needless to say, I’ve wanted to be very well-informed on the topic before weighing in with my opinion (one reason why it’s been several weeks since I last wrote to you). As I was writing, New York Times came out with their own front page article on the topic featuring a case in Johnson City, just a county over from me. Biosolids must be top of mind for many, and rightfully so.

My approach when considering much of the world’s complex issues is to focus on philosophical intention and real-world practicality. As such, my guiding questions while crafting this post were: What do we truly want from biosolids, and how can we possibly achieve it?

If you have thoughts of your own, I hope you feel comfortable to share them respectfully in the comments.

What are Biosolids?

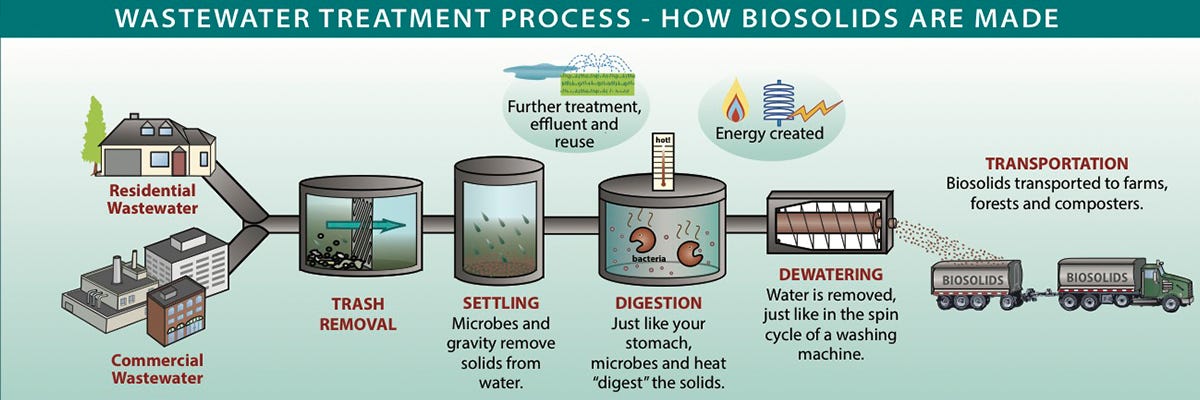

Biosolids are essentially the treated byproduct of material that’s removed from wastewater.

We used to dump this “sewage sludge”, as biosolids were formerly known, into the ocean. This practice was outlawed as part of the Ocean Dumping Ban Act of 1988 prompting an increase in recycling municipal sewage sludge for use on land.

Throughout the 90’s sewage sludge was repurposed as “fertilizer” and spread across agricultural soils or used in municipal soil fertility programs - practices supported by the U.S. EPA. Around this time the more palatable term, “biosolids” was introduced to help shift public perception and highlight the potential benefits of the material rather than its unpleasant origins. Despite the rebranding, biosolids remain controversial today.

The Challenges

Anything that goes down the drain—whether from toilets, sinks, sewers, or industrial processes—is handled by wastewater treatment facilities. These facilities clean the water by separating out a wide range of wastes through a series of complex steps including screening, settling, skimming, microbial digestion, and dewatering.

Wastewater treatment plants are a remarkable engineering feat. They excel at purifying water and returning it to water bodies, helping to keep surface waters as clean as possible. Increasingly, this treated water is also being used in reuse programs, as it’s proving to be as clean as the water originally delivered to our taps.

If the only waste to separate out was organic - leaves, food waste, manure - and the only environmental and public health concern was pathogens, we wouldn’t have many worries about biosolids. But that’s not the world we live in.

Consider the sheer variety of substances entering wastewater treatment plants: chemicals from lawn care, household cleaners, personal care products, agriculture and industrial byproducts; microplastics from washed synthetic clothing and plastic dishes; pharmaceuticals contained within human waste; oil, paint and countless other sources of hazardous waste.

While treatment facilities aim to remove much of these contaminants, nevertheless the primary concern with biosolids today is the accumulation of both known and unknown harmful chemicals in the final material that is then spread across land, namely food producing and recreational sites.

Smells like Greenwashing

The U.S. EPA regulates many well-understood contaminants of biosolids under the Part 503 Rule, like heavy metals, arsenic, lead, mercury and other pollutants. They also regulate for biological hazards like fecal coliforms, common human pathogens and vectors of disease. They even aim to minimize nutrient runoff through reasonable application rates and “nutrient management plans”.

Nonetheless, there’s a significant risk that other, less recognized contaminants may persist without comprehensive monitoring or regulation. This is particularly true for the much-talked-about PFAS (polyfluoroalkyl substances), often referred to as "forever chemicals", which are not yet fully regulated in biosolids despite their potential health risks.

While biosolids are the byproduct of responsibly cleaned wastewater, they themselves are not the environmental solution that some industry websites suggest through over-the-top greenwashing. Rather, biosolids are a significant environmental problem that, in my view, unfairly burdens wastewater treatment plants.

Let’s be clear: biosolids are not inherently a tool for soil restoration—they're a substrate that requires remediation itself.

How bad is it?

Banning the dumping of sewage sludge into the world’s oceans rightfully brought the issue of contaminants closer to our doorstep and it’s not been without casualties.

For some farmers and ranchers, the consequences are severe, with off-the-charts PFAS readings, dead livestock, depreciated land, contaminated food and businesses forced to close. As if agriculture wasn’t hard enough.

Furthermore, there appears to be little to no government support to help these food producers remediate their land or rebuild their businesses, while the industries responsible for producing these chemicals in the first place seem largely protected.

Our Guiding Questions:

What do we want from biosolids?

What most people want from biosolids is pretty simple: to safely close the loop on a major human waste stream.

Can we achieve it?

To do so we have to reduce contaminants at many different levels, starting with their source. From there, I believe there’s potential to better leverage microbes in the treatment of biosolids, to prepare them for safer and more successful land application.

It's important to recognize where we’re currently at in the journey toward not only safe biosolids but also creating higher quality compost. We have a long way to go in developing better soil amendments from our waste streams, but with greater awareness and care, I believe it can be achieved, and in practical ways.

Proposed Treatment of Biosolids

If I were required to use biosolids today, my approach would be to contain them in a heap about three feet high, containing a runoff buffer zone, then heavily amend them with diverse microbial inoculants (and by that I mean truly diverse compost extracts). I would also implement a round of phytoremediation* to mitigate risks and prepare the substrate for use on degraded land.

*i.e. planting into the heap to allow a generation of plants to grow—this serves both as a biological assay and a remediation technique.

Additionally, some biosolids could be used to create biochar - this is not ideal at scale as pyrolysis can contribute to air pollution, but this could play a small part in addressing the most complex cases of contamination.

Knowing that it could take a long time to transition to more responsible manufacturing materials and practices, my proposal is to treat biosolids like a substrate that needs further stages of remediation before being used on land.

Concluding Thoughts

While the intention of biosolids use—closing the loop on a major waste stream—is positive, we still haven’t figured out how to handle the waste responsibly.

If you search scientific literature you’ll find evidence on both sides of the biosolids debate. Some studies highlight their role in promoting soil health, while others point to toxicity and contamination. Biases, such as funding, may play a role, but it’s also likely that the composition of biosolids varies. Some batches may carry more risks than others.

Whether it’s microplastics, trace metals, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, or PFAS, focusing on which contaminant is the worst misses the point. The real issue is that the overall risk is higher than it should be, and we could do better. But it’s difficult since the problem is outsourced—passed from industrial plants to consumers, wastewater treatment facilities, and eventually to farmers, ranchers, and the public. And no one upstream seems willing to take responsibility.

Ultimately, contamination is a societal challenge that requires collective accountability, not just placing the burden on waste management. Solving this will take integrity, better policies to reduce contamination at the source, and a healthy dose of beneficial soil biology to handle the rest.

Thanks for reading my thoughts on this big hairy issue! I’d love to hear from you - have you had experiences (good or bad) working with biosolids?

-Andie

PS: Changes at Home

While public outcry against the companies who developed PFAS having known the risks is more than deserved. It might feel empowering to consider where we have some individual agency.

Consider this bleak quote:

PFAS levels in Massachusetts Water Resources Authority [biosolids] are not much different from levels in food waste compost or septic systems. Levels in household dust are four times higher and a more likely source of exposure.

Quote sourced from: https://www.nebiosolids.org/pfas-biosolids

While this fact is offered as a mode of absolving biosolids, it ought to provoke greater concern for the products we bring into our homes and put on our bodies.

Not to be alarmist, but we live in the time of unsustainability - industries of all kinds flippantly use materials that will not readily breakdown. As the generations that are understanding the effects of that, we should be questioning what’s a ‘necessary’ use of plastic or harsh chemical, and what’s not.

So, I encourage you to start a cultural shift right at home - where can you reduce plastic in your daily life? What household and personal care products could be swapped for an alternative that’s friendlier to you and the planet?

I say this as someone who has a long way to go. 🙏

Where are you on this journey?

Any recommended resources for the rest of us?

Thank you for writing your take on this. This is a subject I have been pondering and researching on for a bit. Love the idea of further remediation but with phytoremediation would the plants accumulate some toxins (metal and chemical?) and become a waste product you’d have treat as a hazardous waste or can it just be tossed back in to a new compost pile? Do you have a list of hyper-accumulating plants one would use for this process? If the plants grow with signs of PFAS damage would you just toss it all and start again with a new batch?

Excellent invaluable topic. I have thought about all of the stuff that we don’t want in our biosolids. America, of course is the worst. A friend of mine created an Eco park in Tijuana and he said that the black water coming out of the Paula above on the hill was far more, powerful and nutrient nutrient laden than the stuff coming out of Beverly Hills. I wish farmers in the Midwest see that their desert of defining their soil. I guess they’re so caught up with next seasons crop to get by.